1966 should have been great for the Beatles. Just before the new year, they released Rubber Soul, a stunning creative leap, and they followed it up with the even more dazzling Revolver in August. It was a one-two punch that rocked the pop world.

This story originally appeared in Volume 15 of Road & Track.

Across town, Mick Jagger furiously cribbed Paul McCartney songs. Brian Wilson of the Beach Boys, whose sublime Pet Sounds came out between the two Beatles LPs, engaged in creative mortal combat with McCartney and had a mental breakdown. An entire generation of rockers was taken to school.

But for the Beatles, ’66 was a nightmare. Days after the release of Revolver, they embarked on a world tour so disastrous, the Philippine army chased them, Japanese crowds nearly trampled them to death, and evangelical Americans burned Beatles memorabilia after John Lennon said the band was more popular than Jesus. By the time they closed out the tour at Candlestick Park, they were cashed. They never toured again.

Back in England, they took a month-long break, hitting the Soho clubs, smoking weed, dropping acid—you know, Sixties stuff. But McCartney, that relentless overachiever and the only driving enthusiast in the group, looked at the Aston Martin DB5 in his London garage and did what you and I do when we want to clear our heads: He went on a solo road trip. No Beatles, no girlfriend, no fans, no dog, no roadie, not even a guitar.

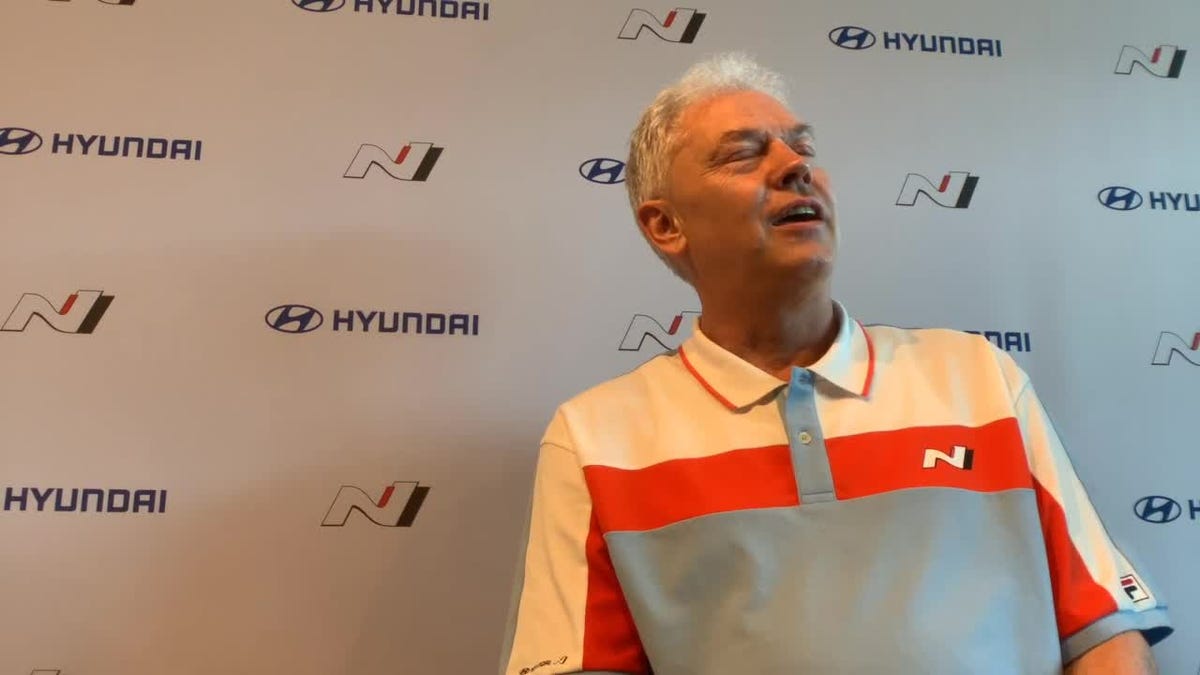

But taking a solo road trip wasn’t easy for a Beatle in 1966—especially one driving an Aston Martin DB5. So McCartney consulted with the costume department from the sets of A Hard Day’s Night and Help! They fashioned a fake goatee for him and designed a Vaseline-slicked hairstyle. McCartney drove the DB5 from his London house to Lydd Airport in Kent, where it was loaded onto a Bristol Superfreighter air ferry, and sipped wine during the 45-minute flight across the channel to France.

He watched the DB5, with its beefy 4.0-liter straight-six and timeless curves, roll down the ramp in the breezy summer heat. “I was pretty proud of the car,” said McCartney, who was all of 24 years old that August. “It was a great motor for a young guy to have.”

After clearing French customs, McCartney opened the Vaseline jar, combed the goop through his hair, adjusted the rearview mirror to center, and affixed the goatee with costumer’s glue. He then fired up the engine, slotted the five-speed ZF manual into first, and tore off down a succession of country roads that cut through cattle farms and fields of haricots verts. He stopped for coffee in quiet villages and pretended to read Le Monde. He smoked cigarettes, jotted in his journal, and presumably stroked his goatee like a normal non-Beatle. These were revelatory hours for McCartney, who hadn’t been alone for six years.

“I was a little lonely poet on the road with my car,” he said. “I’d cruise, find a hotel and park. . . . I would sit up in my room and write my journal. . . . I’d walk around the town and then in the evening go down to dinner, sit on my own at the table, at the height of all this Beatle thing. . . . re-taste anonymity . . . and think all sorts of artistic thoughts like, I’m on my own here.”

And so it went for two weeks, just McCartney thinking artistic thoughts, wheeling a DB5 from town to town, adjusting his goatee. His plan was to drive to Paris and Orléans and follow the Loire to Bordeaux, where he’d arranged to meet Beatles roadie Mal Evans at the town square.

A seed had been planted in France at the wheel of the DB5. On the flight home to London, as Evans slept, the seed germinated. Watching the evening lights of Europe pass beneath, it came to McCartney: The next Beatles album—what would be the greatest rock album ever made (go on with your wrong opinions)—wouldn’t be a Beatles album at all. Instead, four musicians would be the backup crew for a fellow named Sgt. Pepper.

And that’s why we take road trips.