Even though I never got a driver’s license, my father is a car man, has been his whole life. I can always remember him tinkering in the garage, watching racing on TV, driving around in whatever pride and joy he could afford at the time, or couldn’t really but bought anyway. My memories of my father and my memories of cars and my memories of where I grew up are all the same memories. I was born in 1993 and ever since I was born, stock car racing was on television. My earliest memories are fused with the sound of Darrel Waltrip’s yeehaw voice, the grainy television footage of the TNN channel, the hodgepodge graphic design of Nineties NASCAR. There is not a Sunday that went by bereft of these things, not a Sunday without my father laying on our southwestern-patterned sofa watching the race and occasionally napping in the middle of it.

About half a year ago, I realized I didn’t know so much about my father. How he got into cars and why. What he did all those years before he worked at a desk looking at spreadsheets full of medical equipment. What he thought of the same elements of motorsport that for me were so integral to my conception of where and how I grew up. When the opportunity arose for me to write about the Chicago Street Race for Road and Track, my editor let me take my dad, now seventy-three, with me. It had been almost 17 years since we had gone to the track together, a time spanning the misery of middle school to my becoming a writer, a time spanning the beginning of the decline in NASCAR viewership through the advent of its newest iteration in Chicago, a place that couldn’t be farther from the South if it tried. To say that everything had changed is an understatement. Too much had happened and even more had disappeared. But in spite of all this, there we were, me and my father like echoes from the past, sitting in a pair of beach chairs in Grant Park, ten feet from where cars were pulling sound and speed out of thick, humid air.

Back in the day, stock car racing used to be made from actual stock cars, which appealed to my father’s tinkering senses, a mechanic and Navy civil engineer. The ad-hoc nature of the business kept its spirit after it was largely professionalized into NASCAR. Motorsport was simple to understand – one guy won. The championship was won by whoever had won the most in the season. But it was during the Nineties when the sport entered a golden period of popularity, buoyed by drivers like Richard Petty and Dale Earnhart who had reached icon status and who had permeated popular culture.

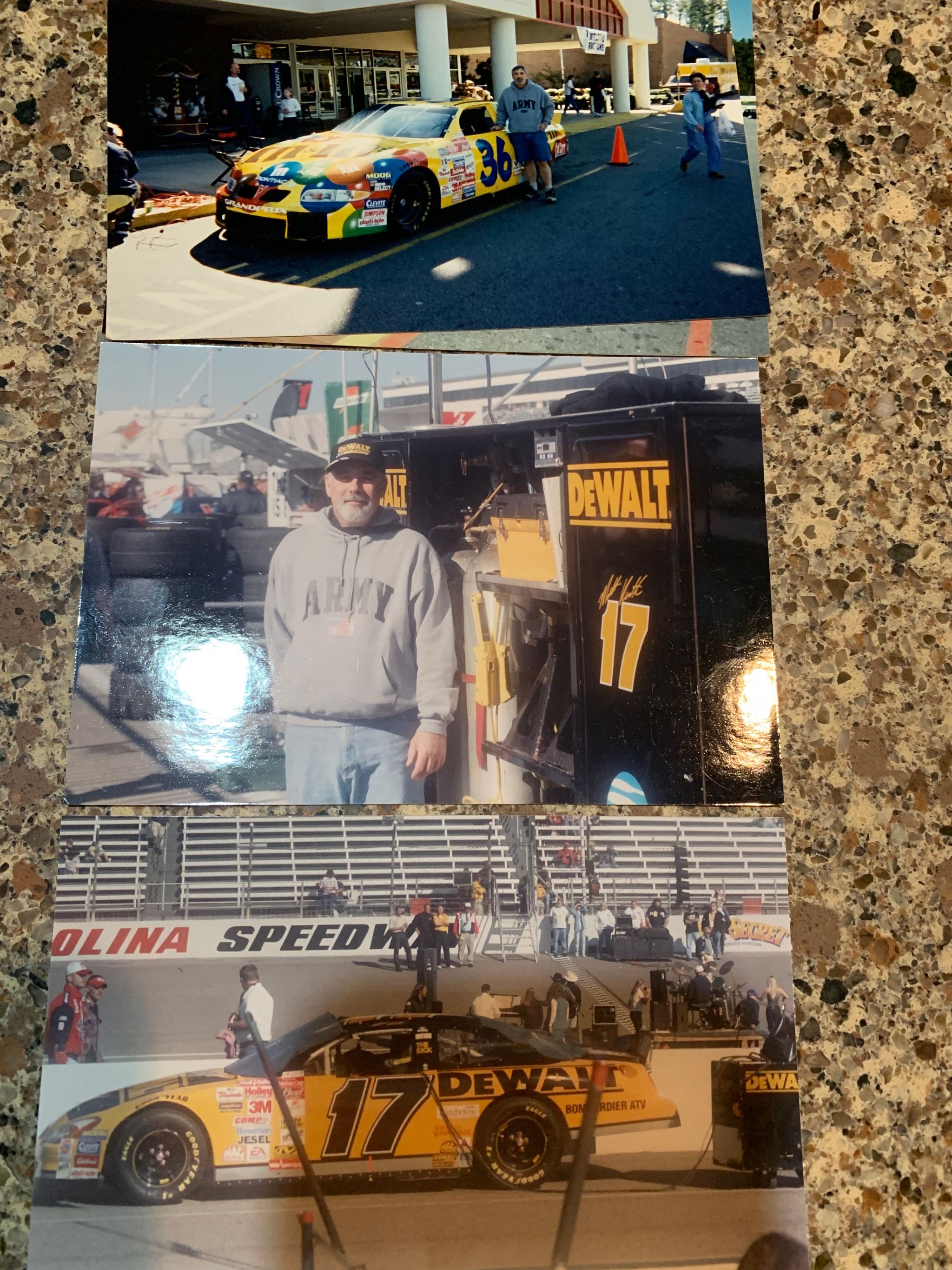

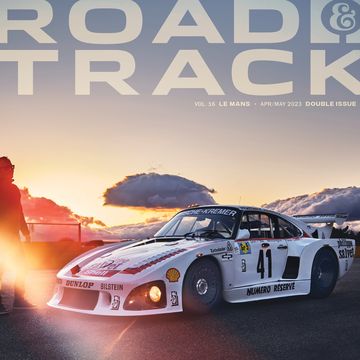

In rural North Carolina, where I grew up, NASCAR was a pattern of life, especially in the Sandhills. About 40 minutes away was Rockingham, The Rock, a tight, high-banked track more reminiscent of a velodrome than a place to drive cars. And everytime they raced at Rockingham, traffic was backed up all the way from there to Aberdeen, a town next to ours where most of the drivers and staff stayed because, to be honest, there was nothing in Rockingham other than the Rock and wide open stretches of longleaf pines. The blessing of being a NASCAR encampment came in the form of Meet and Greets in the K-Mart parking lot. That’s where my dad met Darrel Waltrip once, got a little diecast car signed that’s still somewhere up in the attic. There’s a box of photos of my sister and me in front of promotional cars, the number 4 Kodak which was driven by Sterling Marlin at the time. I recall being mesmerized by the same netting on the windows used to make the jungle gyms at fast food restaurants and the hollow, empty interior not un-similar to the project Volkswagen my dad kept on cinderblocks in the garage.

On the sofa, watching a replay of the 1997 Goodwrench 400 at the Rock, dad tells me about reading Road and Track as a boy, tracking the adventures of Jackie Stewart in Formula One. As a boy growing up in West Point, NY, he’d go out drag racing with his brother, tinkering on cars til midnight, but it wasn’t until he lived in North Carolina that he started thinking about NASCAR. When you went to the Rock, he told me, you’d have to pee before you left because there was nothing between the Rock and Moore County, where we lived. If you wanted good parking you could pay a farmer to let you park in his driveway. There used to be a place called the Lobsteer Restaurant where the drivers and TV guys went to dinner. It’s now a novelty knife shop. “It wasn’t until seeing the cars and feeling, you know, talking to people who were, who were really into it. I became a fan. Then I went to the Rock and became an even bigger fan.”

We were Ernie Irvan fans at home. “I liked Ernie because he was a bit of a wild child, you know? He wasn’t a pretty boy. And he drove for Rauch racing, when they were really good.” Dad liked the way Irvan almost died and then came back and won Daytona. I did too. One day he came back from The Rock with a Texaco jacket, now in the possession of my sister. For the Street Race, I got us both vintage Irvan shirts from eBay. I told my dad I credited NASCAR with everything from weird brand loyalty (I still use Tide detergent) to my love of graphic design. I used to root for Jeff Gordon even though my dad hated him because he drove the psychedelic rainbow DuPont car. Maybe, I said, old NASCAR was so iconic because there was nothing else like it and because it was simple to understand, even if the tactical nuances were known only to enthusiasts – something, including the long-form broadcast I would take with me when I began covering professional cycling. Big personalities were involved, mustachioed cowboys with thick southern drawls. It was irrevocably of the South and one of the few cultural exports from where I grew up. It was something I did with my dad, going to the Rock or to Dover near where my uncle lived. The brightness and brilliance of the cars flashing by the grandstands, the tall spire with the numbers of who was in the lead, the tents selling merchandise, the diecast cars that littered the house when we were young. This was the singular major sporting event I went to. We didn’t have major league baseball. The Charlotte Hornets were in Charlotte, three hours away. There was golf, but we weren’t from the golf playing class. There weren’t any other sports that came to visit us, and that’s true of a lot of places where NASCAR went in the South, not just the Rock: Darlington, North Wilkesboro, nothing towns with nothing in them.

All that began to change in the early Aughts.

Sports are a culture. They change with culture. When Winston pulled its sponsorship of the Winston Cup Series in 2002 due to the tobacco lawsuits and subsequent bans, the culture changed. Smoking disappeared almost entirely from public life and a cell phone company, NEXTEL, itself a remnant of another time, entered the picture. When NASCAR got together and panicked that the ratings were going down, they came up with the rather perplexing idea of having playoffs, aka The Chase, complicating what was initially a simple sport. The rules of NASCAR have only since gotten more arcane, involving stages, and borderline unnavigable point assignment systems that change the strategies of racing in ways I admit I don’t quite understand. Even in those days, however, we still watched. Some things got better. The cars, my dad said, got safer. He said Dale Earnhardt would have lived if he had the Hans device, the device which keeps the driver from breaking his neck in case of impact. Retro guys like Ernie Irvan started to disappear as the sport cleaned up and professionalized, replaced by clean-shaven drivers like Jimmy Johnson. But the biggest change was the elimination of some of those small southern tracks. In the late Nineties, they closed North Wilkesboro and in 2004, they closed The Rock. Matt Kenseth, who my father liked despite his tight-lippedness won the final race there. Then the traffic stopped coming on Sunday. The cars stopped rolling into the K-Mart parking lot. The extraordinary event no longer rolled through our town with its colorful trailers. The town was changing too. After 9/11, it became a de facto exurb of Fort Bragg, 45 minutes away. Gone went the Kmart where the cars and traveling stage shows used to take place. It took them several years to finally replace it with a Kohl’s-Ulta-Hobby Lobby strip mall. Gone were the days where, as a child, I played in the dirt and liked NASCAR and snakes and lizards. Brands disappeared, merged, were outsourced – especially in 2008. The Kodak car went away. Pontiac folded. For me personally, in the mid-Aughts, in a far cry from a childhood awash in the educational media renaissance of the Nineties which saw genderless toys and an emphasis on learning through books, software, and series like The Crocodile Hunter, the laws for cable television changed freeing it of educational requirements and ushering in the era of reality TV. Suddenly expectations for young women went from being a marine biologist to being sexy, skinny, and rich. NASCAR was replaced with MTV, Ernie Irvan with Paris Hilton, childlike wonder with assimilation. None of this was so acutely felt as it was the last day I went with my father to the track.

In 2007, Dad promised to take my sister, a tomboy who was still into NASCAR in a big way, to Darlington as a late Christmas present. My mom and I went instead to the mall. It is not possible to convey how miserable I was on a human level. My heart was not in pop music, low-rise jeans, Abercrombie and Fitch. I was still a child and I think I knew this even though everyone around me was growing up faster than they should have. When me and my mom went to the mall, we went to Aeropostale where I tried on bikinis. Even though I was underweight, ribs showing, through distorted, television eyes, I saw a fat girl. Usher songs about having sex played on the stereo. I hated myself and didn’t understand why.

We got done with the mall early. Dad and my sister were still at the race, so my mom scalped us tickets at the entrance and went inside. The sound rippled through the sky before you could see anything. We walked through a dirt track with vendors lined up for all the different drivers and found my dad. There were about 50 laps to go in the race, which took place at night. The lights shimmered and the rumble could be felt in the chest, radiating through the metal bleachers into the gum of shoes. The shearing sound of speed and the blurring visuals of all those cars had a visceral way of drawing up excitement in spite of my despair and anxiety. What I did not realize then but do realize now, was that this day presented to me two paths in this world, the one that made me unhappy but curtailed abuse, and freedom. It would take years to sort those two worlds out. But I could not at the time admit that I was far happier at the track, bathed in sound and transported to another world, a cathartic and loud one that soothed all that rage, than I was at the mall, picking myself over in the mirror. Jeff Gordon, my old rainbow pal, won that year.

These days, my dad walks with a cane now and he can’t walk far. My husband picks him up from the L station and walks him to our apartment while I’m at the press conference. I’m a sports journalist now, though my sport is usually professional cycling whose press conferences are in unairconditioned primary schools in rural France and not the top floor of the Art Institute of Chicago. The drivers they parade through for the conference, Jensen Button, an ex-F1 guy and Ross Chastain, one of the most dynamic drivers in NASCAR at the moment, show what a different sport this is. Chastain’s penchant for aggressive racing and bumping into opponents is made more possible by the next generation of cars, which are heavier, more durable, and more customized than the NASCAR I grew up watching, not only the era where drivers died but the era in which they survived but their cars were totaled, ripped apart like tinfoil. And there were no street courses to speak of, not in the way Chicago is a street course, pulling its influence from F1’s Monaco or even the many street circuits of Australia’s V8 Supercars series, and charging an exorbitant $465 to sit in the grandstands. (Dad used to pay 30 bucks to go to the Rock.)

At qualifying the next morning, it became clear that my ticket did not include seating. Dad could only walk about four tenths of a mile at a time, so I had to book it to get beach chairs at a nearby Target. It’s a bit chaotic, the logistics of caring for someone and trying to navigate what was in reality a very disorganized event we ended up going home early from because of the threat of lightning. The next day we waited in the house while it rained and talked. I realized viscerally for the first time that my father was getting older. That he was frailer than he used to be. That it could be very possible that this would be one of the remaining times we would spend together going to events. I told him all this, and he said, rather astonished, “I didn’t realize how much all this meant to you.” I didn’t really either.

The way the Chicago race unfolded was like a sonata form recap of Darlington. The race started late because of the rain. I didn’t even know if we would make it down there because of the flooding that had taken place in Chicago. We ate dinner. The saving grace of the day was that the race was kind of a shitshow for the drivers who had difficulty on the wet roads and on the 90 degree turns the street course had to offer. It was during a particularly long caution when we decided to go. By the time we would get there with our beach chairs the race was about half over. But once the hair-raising logistics of arriving were taken care of and despite the sopping wet park, the canceled music shows, the disorganized planning and the overpriced tickets, the cars tore across the road one by one and I remembered all of what I’ve just written about as though it were pulled from some secret part of me. My dad and I, dressed in matching Ernie Irvan t-shirts, watched as cars passed ten feet away. Listened to the announcer. Were together, picking our favorite to win, Shane van Gisbergen, the Kiwi driver pulling his way through the ranks on debut. (My dad called him Shane van Cheeseburger.) Even though you couldn’t see what happened in the other part of the track, on the straightaway where we were, the race unfolded in segments. Cars that were once up front no longer showed up and would limp behind, sputtering and swerving. I’d never been so close before. The caution light in front of us would flash and my dad would notice it before I could and speak to me as he did when I was little, caution’s out! The sun dwindled over Chicago. The race was shortened again due to nightfall. Van Gisbergen rounded one corner in second and then came back round in first. A final caution. My dad stood up to lean against the railing to watch them come through one last time, overjoyed at the maiden success of this man we had not known about until a few hours ago. That’s what sport is, that’s what it does – it forms the backdrop of our life and brings meaning to it, and when we are lucky enough to see it with our own eyes, it forms indelible memories which are always far bigger than the competition between athletes. We stood there together, myself a version of him, the sport we were watching, a version of what, from a very distant past, I knew as though it were a part of me. The same but different. Just like people.